India is well known, among many things, for the quality of their sacred rugs. Make sure you read that right. As much as it has been declared the origin and birthplace of the sacred herb, the infamous weed, Mary Jane, I am talking about woven fabric used as a floor covering. We had passed a rug warehouse several times, and had decided to check it out, hopeful that the deals would be so incredible, we could justify the cost of shipping a rug home. I called up Raj, our favourite taxi driver, to take us to the warehouse.  The warehouse turned out to be more of a mansion masquerading as a rug shop. Apparently rugs are a lucrative business in India. Again, check your head, you filthy addict.

As tempting as it seemed, I wasn’t sure I wanted to carry a rug with me on my motorcycle, so we let Raj do the driving, seeing as his wages were so affordable. Observing the ongoing construction project along the main road, I casually commented on this to Raj. Coastal Goa is defined by a main road, that links all of the small communities that bleed together into the larger central Goa area. Several stretches of the road were torn up with deep trenches that ran for up to a kilometer along the side of the road. This added to the mayhem of Goan driving, creating yet another obstacle to avoid, besides the cows, the buffalo, the bicycles, the crazy drivers, the motorcycles, the potholes, and the pedestrians.  Now all of this mayhem was trying to squeeze into 1½ lanes, and nobody drove as though there were anything different. This was India, after all, and danger is a way of life.

Shortly before this, I had been driving my motorcycle to pick up dinner one evening. I was slowing down on account of the buffalo standing in the street directly ahead of me. A man with a small child on the back of his motorcycle was riding behind me, and I guess I had been blocking his view of what lay ahead, for as he pulled past me and accelerated, I heard him exclaim “Whoa Sheet!â€Â I slammed on my brakes as I watched him hit the buffalo side on, and both he and his son went flying over it. I stopped and rushed over to help them, but seemingly out of nowhere, a crowd had gathered and surrounded the two. The boy had a gash on his head, but seemed otherwise okay.  Neither the man nor his son had been wearing a helmet. It dawned on me that the gathering crowd might think that I was somehow responsible for the accident. I had heard the stories of a lynching taking place before the true nature of events were even determined. Fortunately for me, it appeared that the people gathering could sense my concern for the two, and realizing my lack of blame for the incident, waved me away, saying that they were fine and not to worry about it. My relief at not being lynched by an angry mob seemed to dissipate in the afternoon sun, and I rode on, hoping the best for the two.

Back to our rug dealers. As Raj looked at the ditch diggers he noted, ‘They work very hard. They must dig this all up, and fill in every night, and dig up again. Then, they will lay the cable. Next year, maybe they will have to lay new cable, do it all again.’ Part of me wondered how human labour could be cheaper or more efficient than a piece of heavy equipment like a back hoe, so I asked Raj what these people were paid daily. “Oh, about 200 Rupees†came the reply. 200 Rupees. About $5. I wouldn’t let myself be paid that little as an hourly wage, yet here, that seemed enough to maintain daily survival.

Compared to the rest of India, Goa is fairly affluent. Wondering aloud how people could survive here on that kind of wage, Raj replied that most of them were migrant workers, coming to Goa for a short time to make money before returning to whatever poorer state they may be from. To them, this was a wage worth migrating for. And once again, India surprised me with the staggering differences in their reality from what we were used to.

Raj owns a motor scooter repair shop not far from our resort. He also sells gasoline on the side. And drives a taxi. And acts as a tour guide. It is the willingness of some people to diversify that enables them to move ahead in a country with unimaginable competition for resources. And yet it seems that the caste system still creates a ceiling for how high you can reach. And thus there are always those to dig ditches, those to drive taxis, and those to own the land and the call centers. There are no delusions of changing your social status, no matter how hard you work or who you step on as you attempt to climb a ladder with a glass ceiling. It is simply the way of things in India.

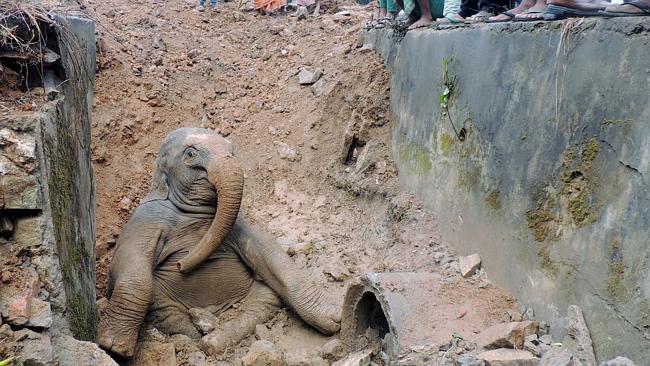

We were in good enough standing with Raj that he was willing to share an experience that transcended the imposed social boundaries, one that most westerners only see as a spectacle from the outside. Ganesh Chaturthi, the annual festival in honour of the god Ganesh, happens every year in early September, lasting for about 10 days. Ganesh is one of the most beloved Hindu gods, being a sweet cherubic childlike figure who was given the head of an elephant after a tragic beheading at the hands of his father, Shiva, after an innocent misunderstanding.

It seems that Shiva was away on a business trip when his wife Parvati created her son Ganesha by breathing life into the Turmeric paste used for bathing in. Setting her new son to guard her as she bathed, Shiva came home to find access to his wife denied by the youth. In a fit of anger, he beheaded the boy, not realizing it was (sort of) his own son. After Parvati threatened to destroy all of creation, and at the urging of Brahma, the source of all creation, Shiva chilled a bit, and decided to bring the boy back to life. He sent Brahma out on a mission to bring him the head of the first creature he found, who happened to be a wise old elephant who offered his noggin. Brahma returned with the head, which Shiva attached to the boy’s body, and breathed new life into it. Sounds a bit like a science fiction story, right?

The boy was given the status as being foremost among the gods, and is revered as the remover of obstacles and ego. He is beloved in Hindu culture and beyond. Ganesh Charurthi is a joyous celebration, where an altar is set around a clay statue of Ganesh. Entering the home of Raj’s cousin, we expected to find a scene of reverence and wonder. We were scarcely prepared for the full set of disco lights adorning the altar while everyone danced around, drinking Coke. After 10 days of revelry around the disco Ganesh altar, the statue is carried to the sea, and set in the water. This would be fine if natural clay was used, but often as not, plaster of Paris is used in conjunction with toxic paints, leading to an increase in toxicity in the water after the festival. The Indian government has been hard at work creating a set of guidelines to ensure that the festival is as wholesome and environmentally friendly as it is fun. Although the Goan Inquisition attempted to ban the ceremony, it lived on in secret, and to this day, many houses will have Christian crosses alongside images of Hindu Deities. Divine wrath is not something to scowl at, and most Goans play both ends against the middle.